The Bayeux Tapestry: A tale of threads and steel.

Friday 27 February 2026

-

Part1: Understanding a great work of European art. It is not a tapestry.

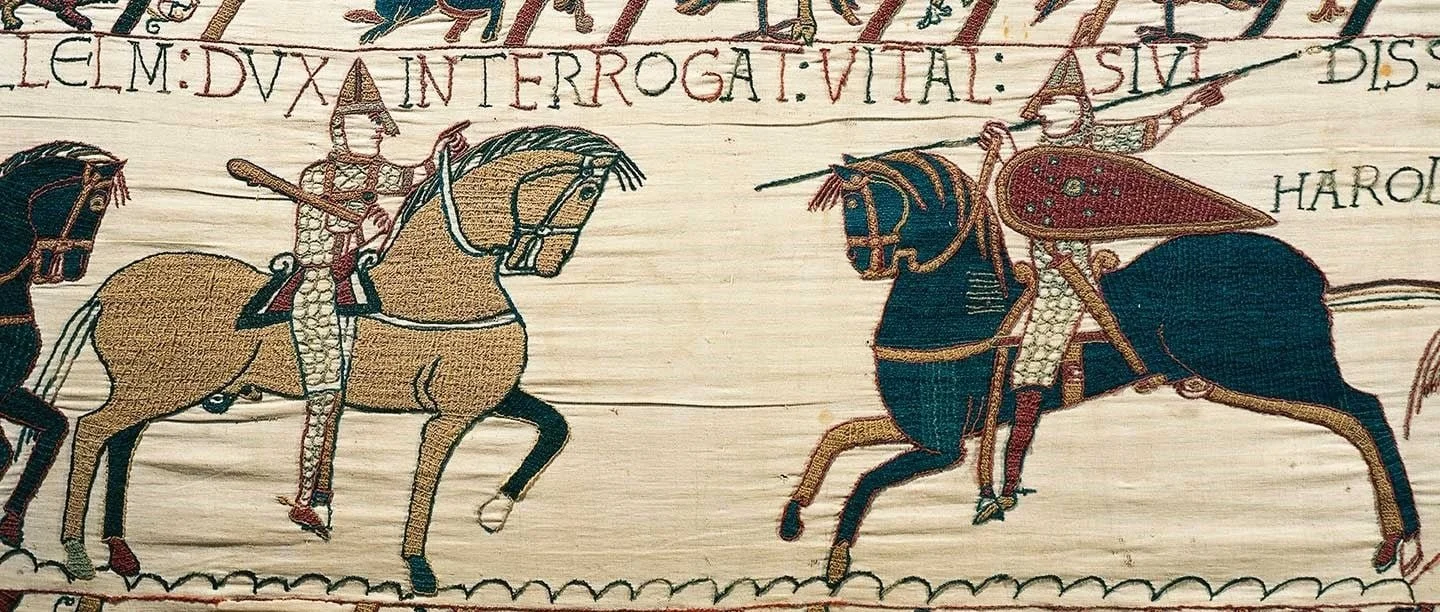

In the first talk of the day, we explore the essential facts of the Bayeux ‘Tapestry’ – what it is, when it was made and how, why such a monumental embroidery was made in the first place, and possibly who made it. We also look closely at how it works, in its telling of the grand drama of the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, and in its form as one of the greatest works of sequential narrative art ever created

-

Part 2: Two Kings, a bastard Duke, some knights, a comet and a dwarf. The story told by the tapestry.

We would know very little about the late eleventh century in western Europe if the Bayeux Tapestry had never existed, or if it had been destroyed in the eighteenth century (which it nearly was). Moreover, we would know next to nothing about what the world of Anglo-Saxons and Normans actually looked like. The Bayeux ‘Tapestry’ (in fact a monumental embroidery) is a unique visual record of cataclysmic historical events that shaped everything about our lives today – from the landscape of the country, to our system of government, to the language we speak every day. In this second talk we follow the story told in dynamic images blow by blow – from the end of the reign of Edward the Confessor, to the initial comradeship of Harold Godwinson and William of Normandy, through Harold’s short reign as King of England, to William’s invasion, conquest and establishment of a Norman royal dominion that endured until King Richard III was slain in battle in 1485.

-

Part 3: The gears of conquest. The Norman knight, his armour and weapons and his representation in the tapestry.

The Norman invasion of England in 1066 is commonly understood as the stage on which the medieval knight made his spectacular debut, fighting on horseback with spear and sword, trampling ‘The Dark Ages’ under the hooves of his warhorse and ushering in ‘The Age of Chivalry’. Although there is some truth to this idea, the honest reality is more complex. Concepts of chivalry can be traced back into the warrior cultures of the Migration Period, while mounted armoured combat was practiced by the Romans and Carolingians, among others. Even so, the Norman way of knightly warfare was indeed new in many respects, as was their use of the image of the mounted knight in their art, foremost, in the Bayeux Tapestry. This epic embroidery employs the knight in armour as one of its most important visual elements. However, because Norman arms and armour are not very well understood by most historians, many of the subtleties of the ‘tapestry’ as a form of graphic storytelling have been overlooked or misunderstood. This final lecture delves deeper into the realities of war at the time of the Conquest in order that we may better appreciate the ways in which the Bayeux Tapestry was intended to be ‘read’ and understood.

Our Speaker: Toby Capwell

Toby Capwell is an independent scholar and leading authority on medieval and Renaissance arms and armour. Over the last thirty years he has worked with many of the world's great collections, including the Imperial Armoury in Vienna, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Royal Armouries in Leeds. He has served as curator of Glasgow Museums and the Wallace Collection, where he worked for 16 years until January 2023. He is a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and a Freeman of the Worshipful Company of Armourers in London. He is the author of many books on armour, weapons and tournaments, has curated numerous exhibitions, and frequently appears in film, television and online media.